Dr Andrew Hillier shows how a recently- discovered collection of photographs shines a spotlight on the importance of family in treaty port China in the early twentieth century.

On 12 April 1899, Edith Sarah Sharples and Walter James Clennell were married in Shanghai’s Holy Trinity Cathedral. Clennell had joined the China Consular Service as a Student Interpreter at the age of twenty in 1888, and, having quickly made his mark, had already risen to the position of Acting Consul.[1] Six years his junior, Edie had also been living in China for some years. The fourth child and eldest daughter of John Sharples and his wife, Sarah (née Mercer), her father had left the family home in Birkenhead in the late 1870s and, arriving in Shanghai, had established his reputation as a skilled engineer. Edie’s mother and at least four of the five children had joined him some ten years later and were all still living in China at the time of the wedding. Walter and Edie would spend the next twenty-five years in the country, a time that is reflected in a rich collection of family photographs. [2]

Unlike the wives of so many consular officials, whose lives have been overshadowed by their husbands’ careers, in this collection, Edie occupies centre stage, along with her siblings and the growing brood of children within the Sharples family circle.[3]

1. Edie’s brother, Herbert and (from left) Hetty (née Heukendorff), wife of Edie’s brother, Ernest, who may have taken the snapshot, Amy (Herbert’s wife), Edie, and ‘progeny’: Jiujiang, c. 1904.[4] CF01-075

As Edie and Walter approached their wedding, the Boxer movement was spreading through the north of China and would leave a bitter legacy and continuing resentment at the Western presence, although some would look back to this time as the golden age of the Consular Service.

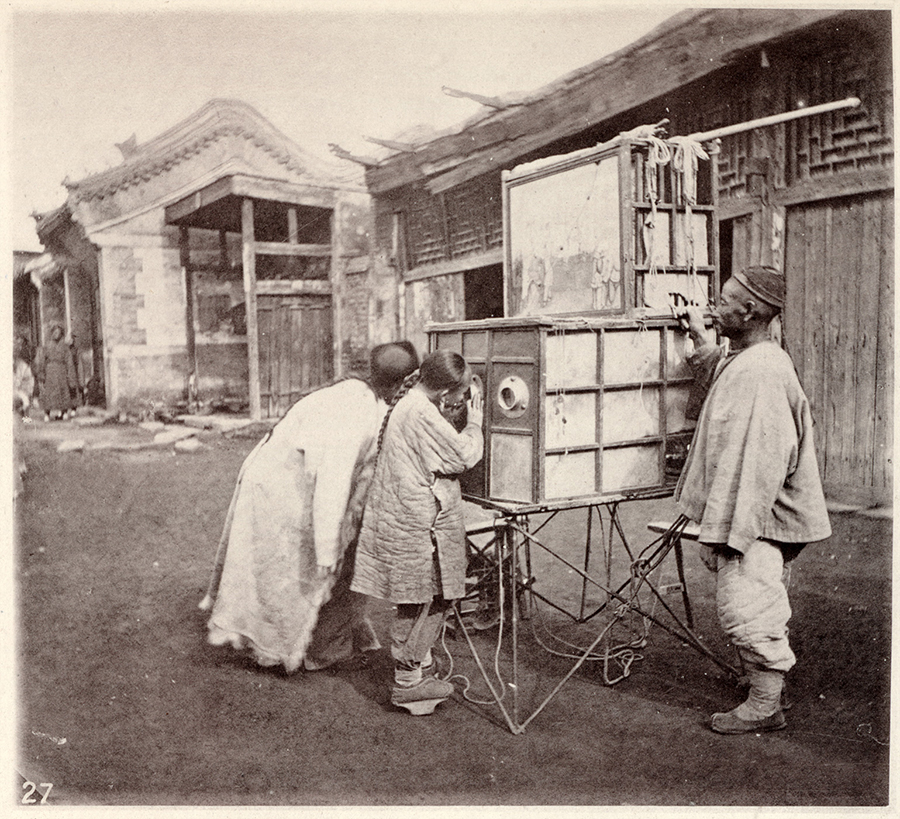

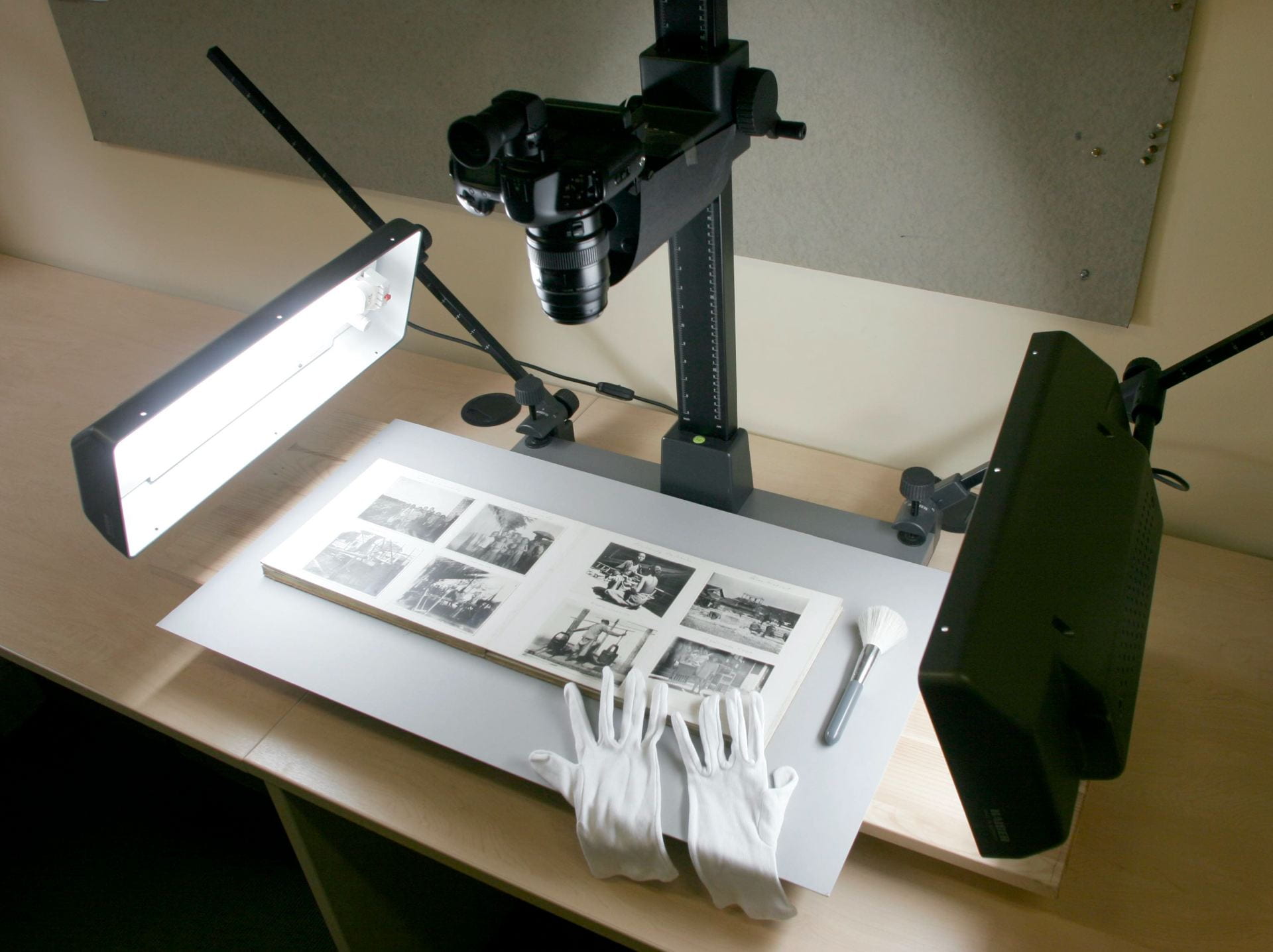

[5] Against that background, family and its practices provided a key mechanism for restoring ‘normality’ to treaty life. In addition to the formal pictures taken by photographic studios- mainly Chinese -, the everyday could be snapped with a hand-held Kodak. Little different to today’s selfies, circulated amongst friends, enclosed in letters home and, as here, pasted into albums, these images, in Robert Bickers’ words, played ‘a vital role within networks of family communications, forming a private economy of exchange and understanding’.

[6] However, despite appearances, these lives were far from normal, spent as they were in ‘alien surroundings far from home … in most abnormal conditions’.

[7]

2. ‘Abnormal conditions’: Walter and Edie and child, setting off on a round of social calls. Given that their little son, Lindsey, died in 1903, either the date is incorrect or, if correct, the child must be May, who will have been aged one at the time. Formally posed, the photograph may have been taken by a member of the consular staff. CF02-05 and 07.

And, for Walter and Edie, as with so many treaty port families, it was a life punctuated by frequent illness, the death of two of their children, extensive travelling and lengthy separations.

By the time of the wedding, the Sharples family had become well-known in Shanghai, not least because of its participation in Shanghai’s amateur theatricals which were enthusiastically covered in the pages of the North China Herald.

3 ‘The Gondoliers’, Shanghai, January, 1896. Edie is on the far right. The photograph was most probably taken by a commercial agency. CF03-004

Although Coates suggests that the introduction first came from Edie’s brother, Herbert, when he was working in Shanshi (Shasi) and Walter had been serving there as Acting Consul, she and Walter probably met in Shanghai, when he was serving as Clerk to the Supreme Court.[8]

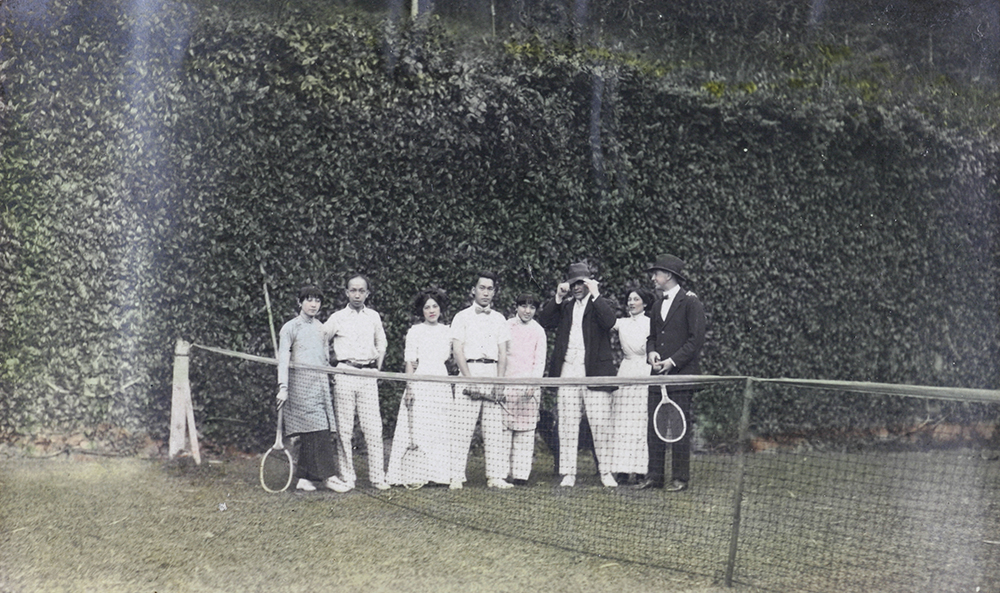

4. An English way of life: lawn tennis in Shanghai – possibly 1898. Edie is first left. CF03-014

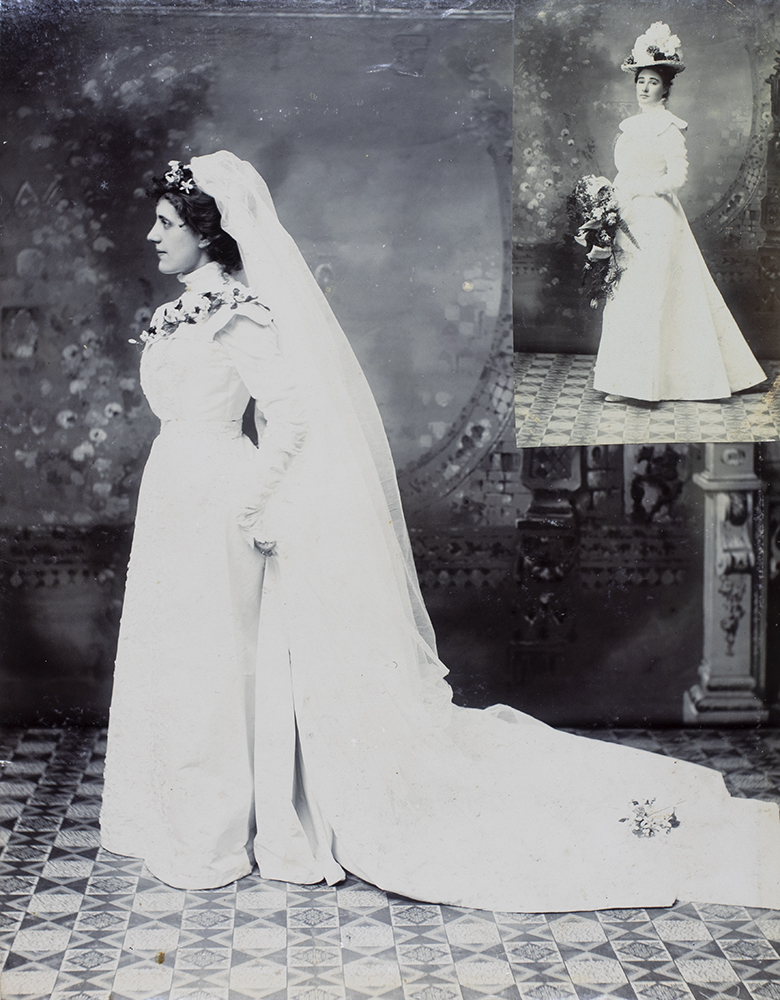

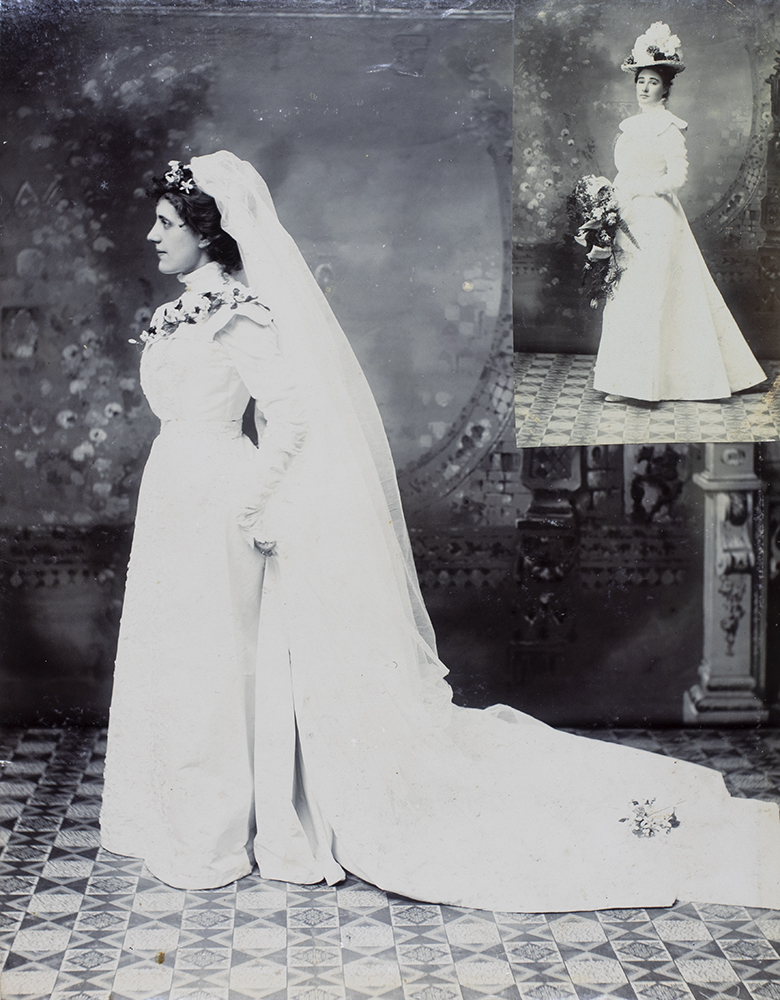

These early days are recorded in a number of photographs which then lead up to the wedding. Attended by her younger sister, Connie, and one other bridesmaid, Edie was, according to The North China Herald, ‘attired in white corded silk rimmed with chiffon’, and was given away by her father in the presence of ‘a numerous gathering of relatives and friends’.[9]

5. Edie on her wedding day, 12 April 1899, with, inset, bridesmaid, Miss Jeffrey. CF03-024.

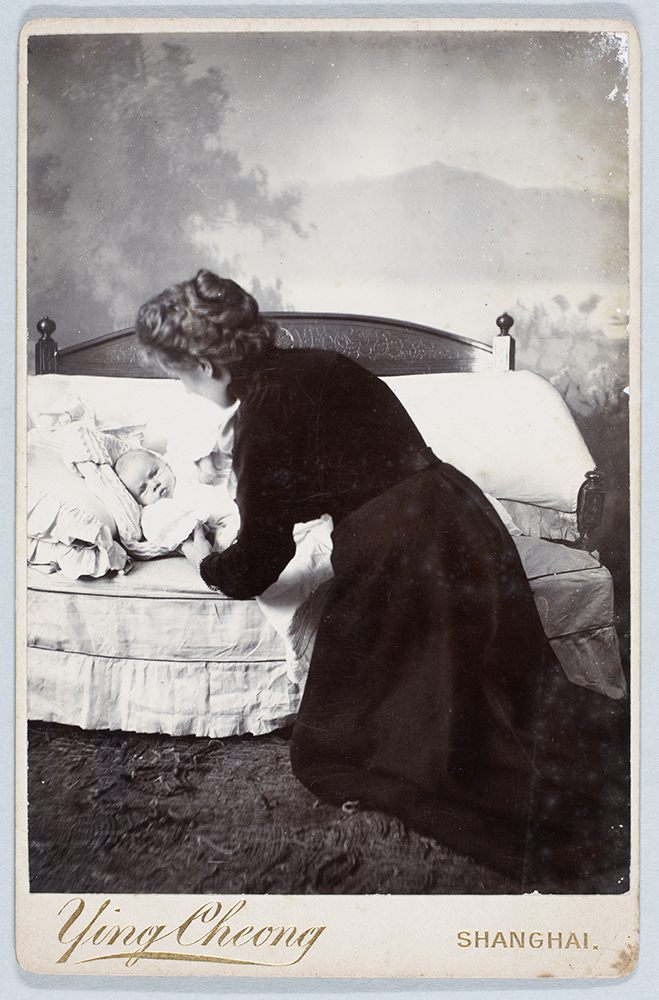

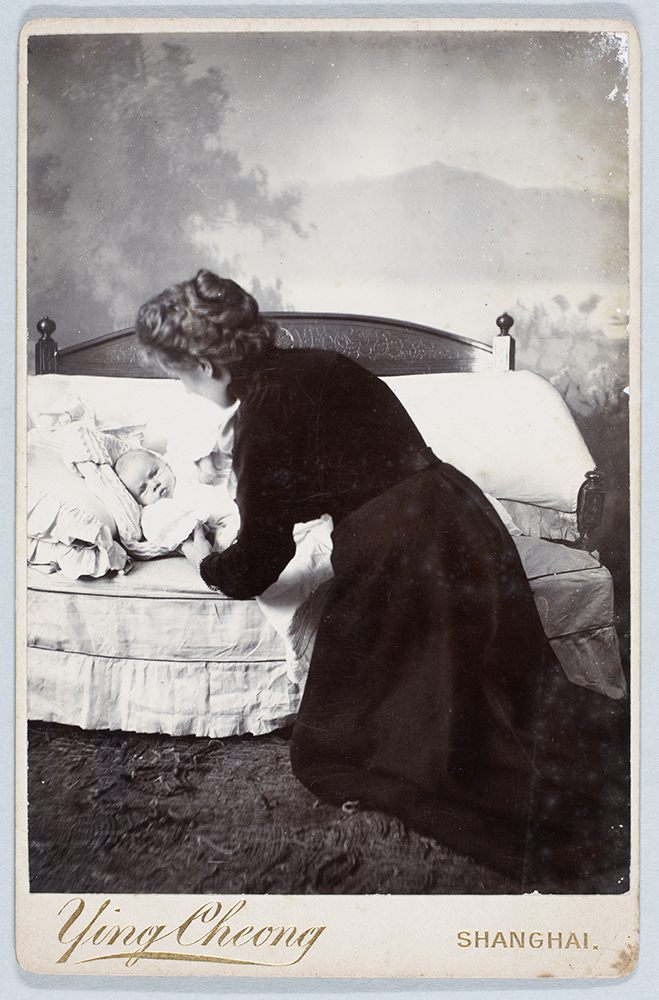

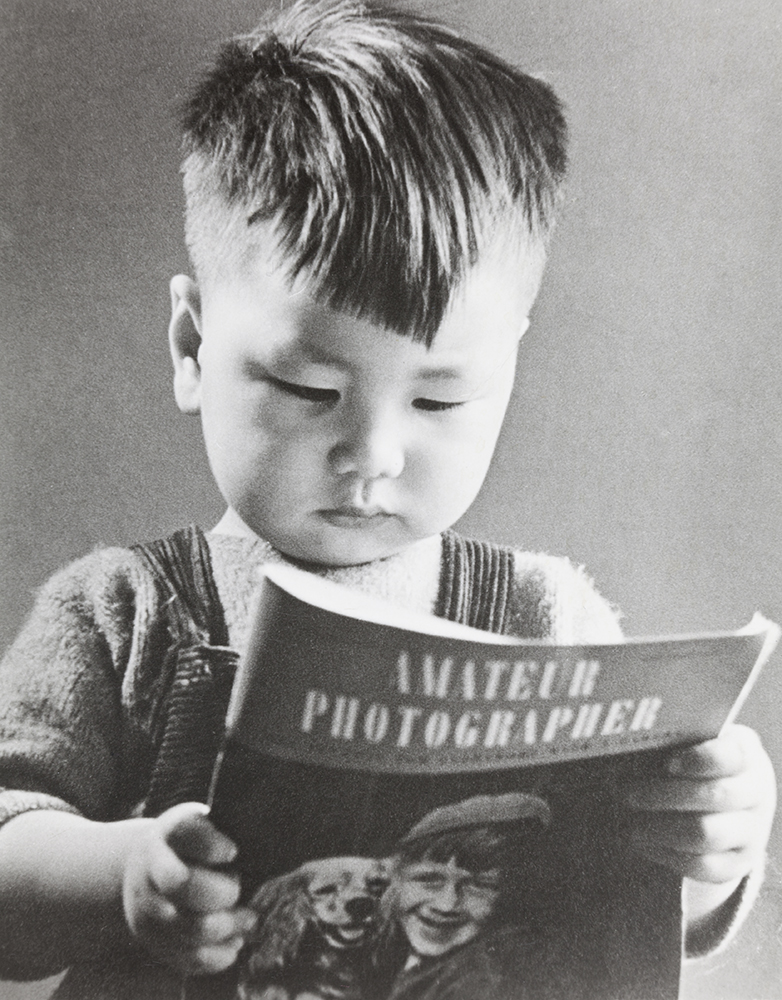

Five days later, the happy couple set off up the Yangzi for the consulate at Wuhu, where Walter had been recently appointed Acting Consul but it would not be for long, as, soon afterwards, he was off again, this time to Jiujiang (Kiukiang). Edie was already pregnant and it was there that [Ernest] Frank was safely delivered on 2 February 1900. But the Boxers were closing in and, the following month, together with a number of British women and children residing in Yangzi treaty ports, Edie was collected by a warship and taken to safety in Shanghai. There, little Frank was formally photographed by the well-known studio, Ying Cheong. [10]

6. Frank’s first studio portrait, March 1900 aged one month. CF01-061.

Meanwhile, Walter stayed on to face the music, but, although threatened, the consulate was not attacked and, following the relief of the legations in August, 1900, he and Edie were able to resume their life in Jiujiang. Over the next ten years, he would serve, initially as Acting Consul and, from 1902, Consul, in four treaty ports and during this time, they would have four more children.

The second, [Walter] Lindsey, was born in the summer resort of Kuling (Lushan) in July 1901 and, two years later, Walter and Edie set off for England for their first spell of home leave – furlough as it was called – since they got married. She was pregnant again and May was born in the Sharples family home in Birkenhead in March 1903. However, just a month later, Lindsey contracted meningitis and died, weakened so the doctor said, by an illness contracted soon after birth. Against this melancholy backdrop, Edie was introduced to Walter’s family. Returning to Jiujiang, the photographs were a poignant reminder of their time in England and Lindsey’s short life.

7. Lindsey and Frank, Birkenhead, January 1903. Two months later, Lindsey contracted meningitis and died. CF01-078

Further tragedy was to follow. In June 1905, Edie gave birth to Beryl, once again in Kuling, but the child died within two months. Writing to the British Minister in Peking, Sir Ernest Satow, on the day she died (2 August), Walter said that the child had been ‘apparently healthy and was ailing only since July 28th so that her death is as much a surprise as a shock to us’. Attributing it in part to the unhealthy climate, he asked if he could be transferred to a port out of the Yangzi region.[11] In response, two months later, Satow instructed Walter to open a consulate at Jinan (Tsinan), the provincial capital of Shandong. The purpose, he said, was not so much to perform consular duties as to keep an eye on Germany, which, from its base on the coast at Qingdao (Tsingtao), was rapidly extending its influence in the region. [12]

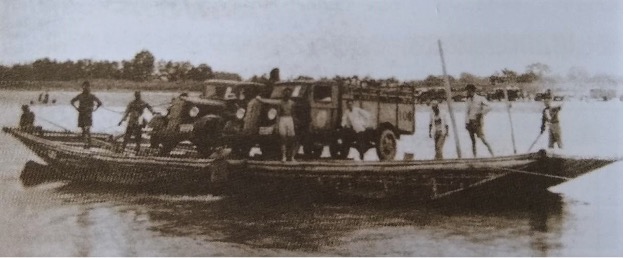

A further private letter from Walter to Satow gives a good idea of the arduous journey the family made from Jiujiang. Having taken the steamer down the Yangzi, they spent a few nights in Shanghai before boarding the Taksang on 24th November for Qingdao. Both Frank and May were ill with bronchitis, Edie had severe sciatica and everyone was seasick. By the time they arrived four days later, May was seriously ill and, so the German doctor advised them, they needed to complete the journey as soon as possible. However, as Walter told Satow, it was bitterly cold and it ‘would have been madness to expose either of the children to the biting northerly wind’ that night and so they left for Jinan by train the following day.

Fortunately, that was a beautifully fine and mild day and the 12½ hours railway journey in a well warmed carriage did them good rather than harm. But there was a chair ride of 4 miles or so from the railway station to this house – and this, in the cold of the evening, brought on a rather serious relapse in the case of Frank. [13]

Terrified that they were about to lose another child, they kept both children in bed and Frank and May slowly began to recover. Although long-term accommodation was difficult to find, by the end of the year, they had settled in.

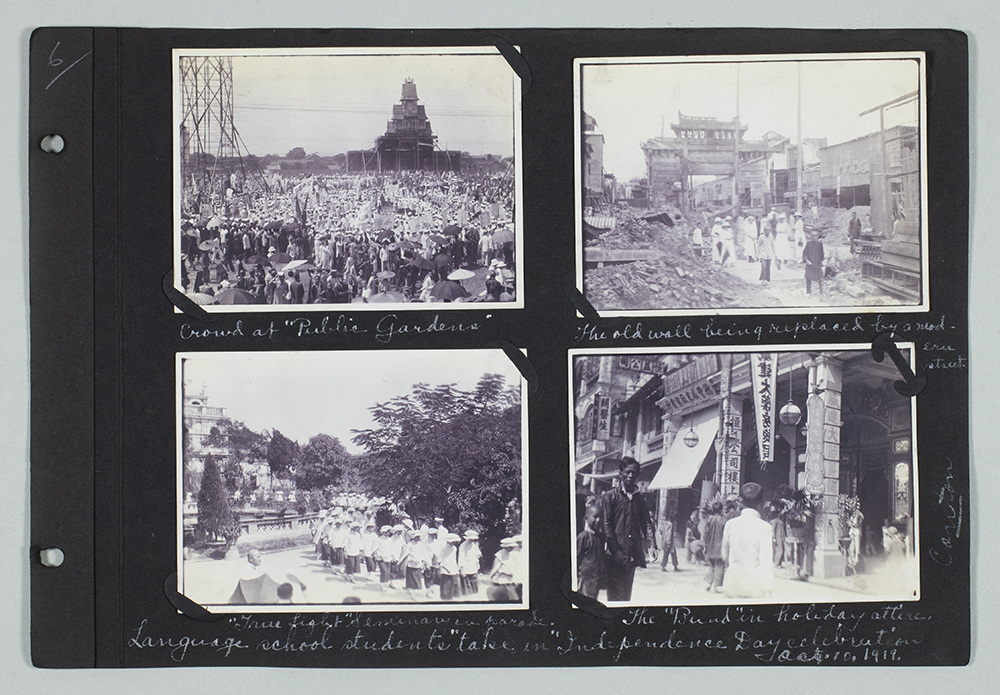

8. King’s Birthday picnic, 9 November 1906. Thousand Buddha Cliff Xino Temple, Jinan (Tsinan). Frank, May and Edie in front. Those named on the back include the German consul, Dr J. Merklinghaus (seated at front on left-hand-side), and other members of the German community, Daotai Chwang and a number of Chinese figures- ‘our number 3 chair coolie’, Monsieur and Madame Li, the amah, and ‘Boy’. Inscribed ‘for Connie’, the photograph seems to have been taken by a commercial agency and to have been sent to Edie’s younger sister.[14] CF01-083

There, in the consulate, on 18 February 1908, Walter John was born. In his engaging memoir, Jack, as he was always known, recalled that the birth had taken place ‘in the shadow of China’s great Holy Mountain, Tai Shan’, which could be seen 35 miles away and this gave him, so his mother thought, ‘an auspicious start in life’. [15] The following year, tired of having too little to do, Walter was pleased to be appointed as Consul to Hangzhou, a port on the Grand Canal, and, once again they were on the move.

9. The Consulate at Hangzhou, 1909, with children seated on the lawn. CF01-001

However, although they were in a fine consular building, the surroundings were unhealthy and Edie and May soon contracted typhoid. While they both made a good recovery, it was decided that Edie should take all three children to England to recuperate. Travelling by the recently- opened Trans-Siberian Railway, the journey was reduced to fifteen days but was still a major undertaking for Edie without Walter on hand to help.

They re-joined him the following year and this somewhat peripatetic life ended in 1911 with his appointment to Yingkou, Newchwang (Yingzi). A remote port in Manchuria, it had a splendid, if bracing climate, with the River Liao being closed by ice from mid-November to mid- March.[16] He and Edie would remain there for the next ten years, save for spending a year’s furlough in England in 1913. Their sixth child, James Geoffrey (Jim), had been born the previous year and, when they returned to China in the Spring of 1914, they brought Jack and Jim with them but left Frank and May to be educated at schools in England, unsuspecting that, with the outbreak of war, they would not be able to re-join them. Boarding with relatives, Frank and May remained separated from their parents for the next five years. Meanwhile, able to run free, and surrounded by friends, Jack and Jim enjoyed what Jack’s memoir depicts as an idyllic childhood.

10. Empire Day at the British Consulate, Yingzi, 25 May 1914. The names are captioned on the reverse side. Edie is seated on the far right with Walter standing behind her. Jack and Jim must be there somewhere. CF01-143 and 144.

Although they were largely unaffected by the war, they had to sever their ties with their many German friends and, as a number of photographs show, the concession was draped with banners reading, ‘God bless our native land’. Busying herself with war work, Edie formed a local branch of the Women’s Needlework Guild, which sent back large consignments of knitted garments for the troops at the Western Front. [17]

11. British women’s war work, Yingzi, 12 January to 17 March 1917. CF 01- 178

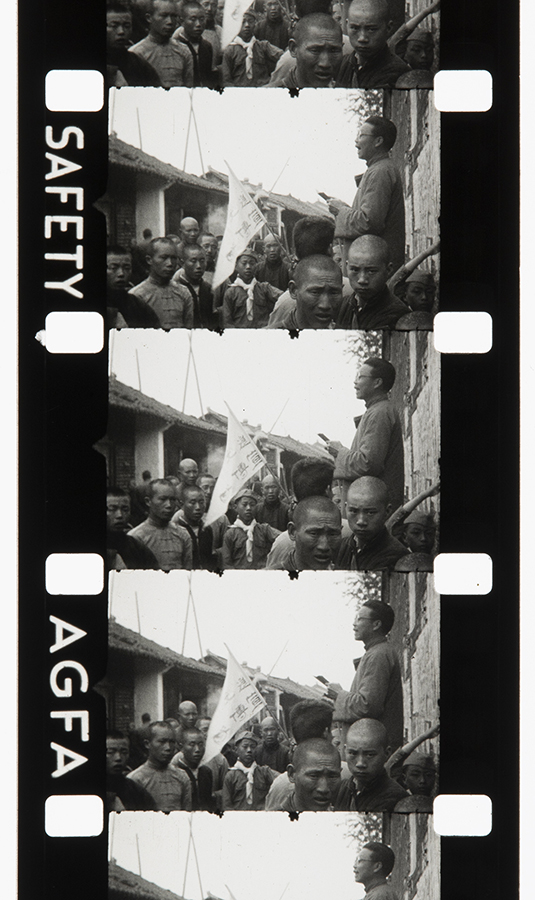

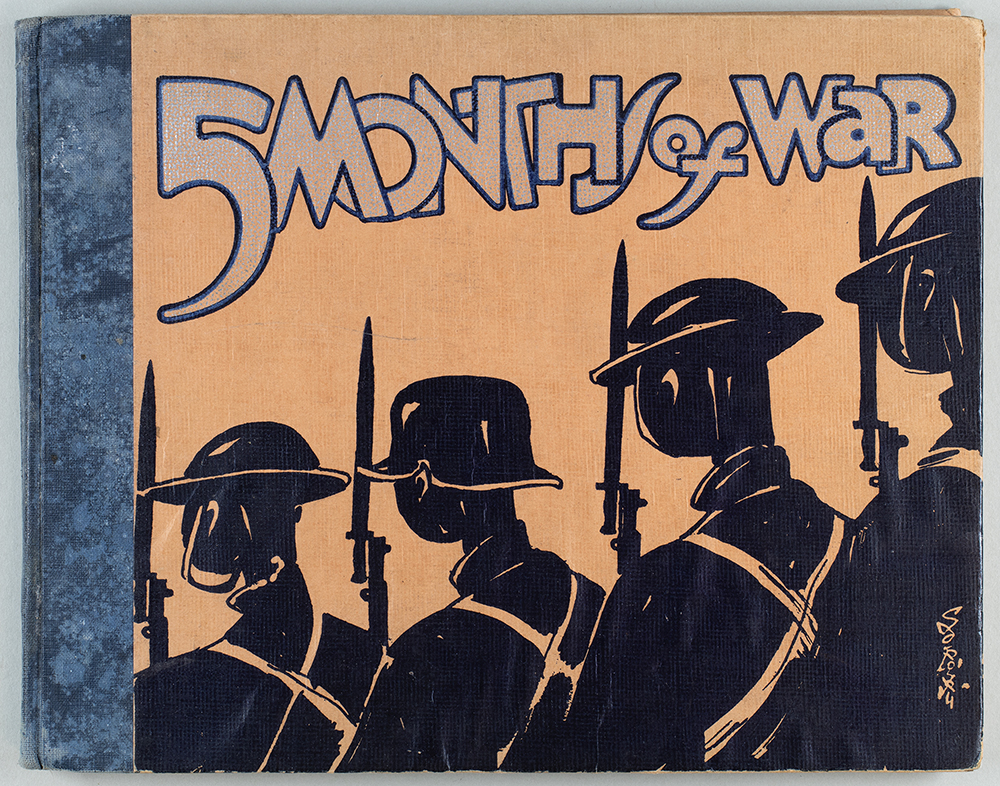

With China entering the war on the side of the allies in 1917, Clennell took charge of recruiting volunteers from the local area for the Chinese Labour Corps

12. Chinese Labour Corps assembled at the Qingdao Camp under the command of Mr Sandbach. The photo was taken by a Mr van Ess and sent to Clennell, whom he knew well, accompanied by a letter praising ‘the smartness of the work done in moulding raw material’. CF01-190 and 191

Walter had become deeply interested in Chinese religion and the family accompanied him as he travelled around the region, visiting temples and chatting to sages. Although remote, the port was frequently visited by warships in the summer and Edie much enjoyed playing hostess to their officers.

In 1919, she and Walter were at last able to take a period of home leave and be re-united with Frank and May. They returned to China the following year, bringing May and Geoff with them, but leaving the two older boys, Frank and Jack, in England. They would only meet again when Walter retired six years later after serving in two considerably less remote treaty ports Zhenjiang (Chinkiang) and Fuzhou (Foochow).

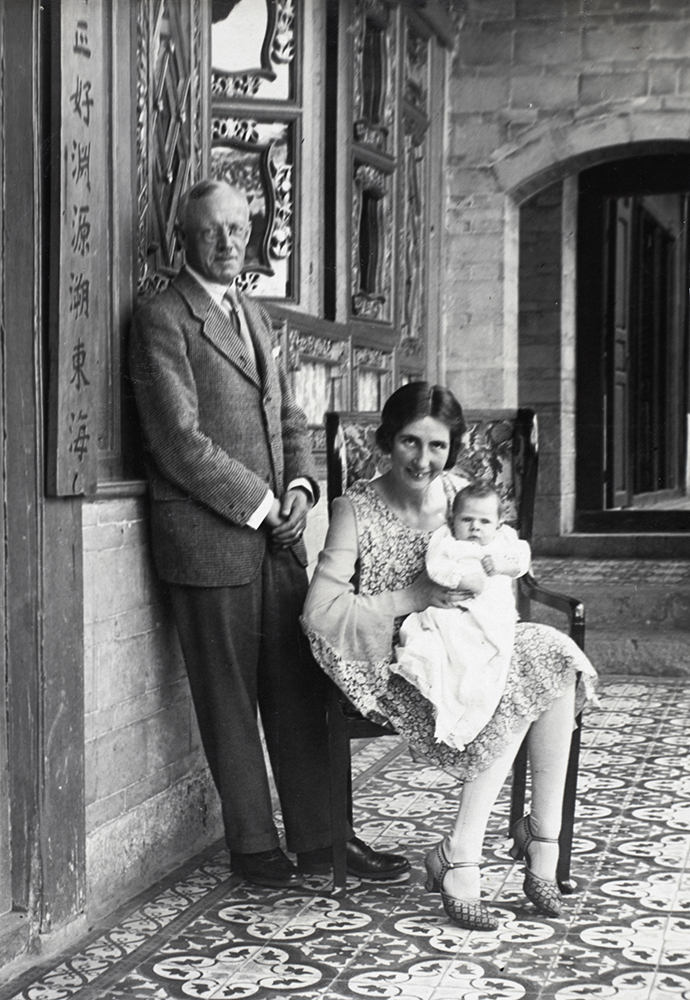

13. May and Edie, Fuzhou Consulate,1922, possibly taken by Walter. CF01-231

Schooled as a Student Interpreter in the late 1880s, Walter had no doubts about the validity of Britain’s imperial cause. However, from his earliest days in China, he had been fascinated by its culture. Having published a history of its religions in 1917, he devoted his retirement to writing a wider study of the country and its people. [18] Having become a recognised authority, in 1928, he was invited to visit Cambridge University and discuss the possibility of his accepting the Chair of Chinese Studies. Tragically, as he made his way from the railway station, he was knocked down by a milk cart and killed. His unfinished history of China now resides in the library of his old school, Felsted.

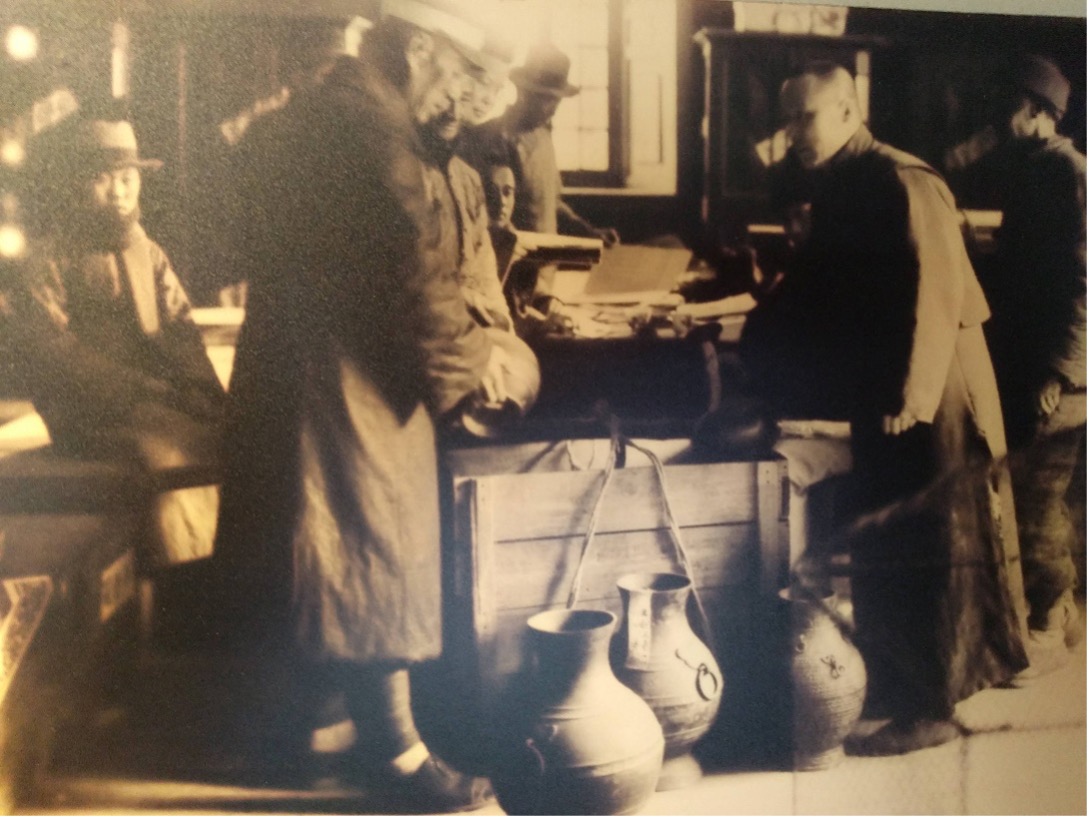

Sharing Walter’s values, Edie had also developed a love of the country and become a considerable collector. She lived on for another twenty-six years in their home in Hitchin. Visiting her in December 1950, the Hitchin News described her, surrounded by Chinese objects and memorabilia, her sitting-room providing ‘a vivid nostalgic glimpse of China, its walls hung with gleaming Chinese tapestries and pictures’.[19] As the article concluded,

her unflagging interest in others enables her to live to the full the spirit of the inscription on the scarlet Chinese visiting card used by her husband on his official duties: ‘Lo Miss Lo’ – ‘he delights in other people’s happiness.[20]

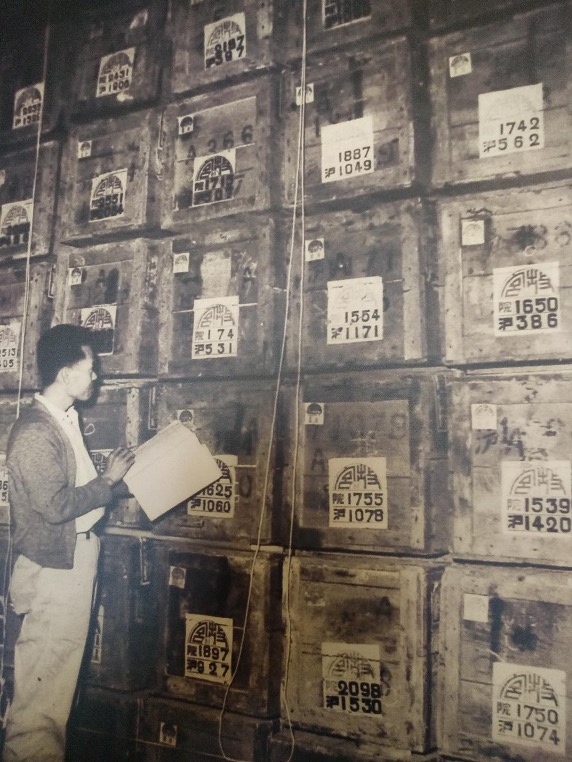

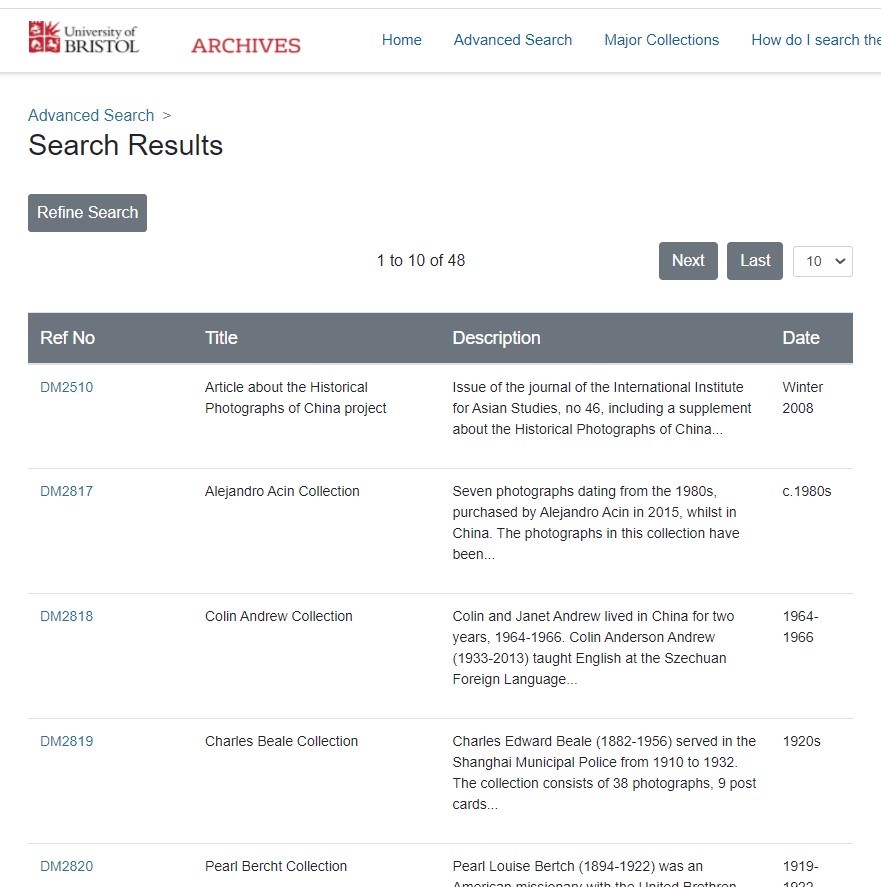

A number of different narratives can be spun out of this collection of photographs. Even though exchanged within only a limited circle, they can be seen as part of what has been called a ‘colonizer’s handbook’ and ‘a documentation exercise that symbolised possession’.[21] Certainly, they served to normalise and reinforce the apparent legitimacy of the British presence. But, they also include images of Chinese people and, while these are formally posed, with our knowledge of Walter Clennell, we can infer that there was an easier relationship with Chinese officialdom. There again, it is clear that none of these people played any part in the family’s day-to-day life and remained very ‘foreign’ to them. When viewing them on that intimate level, we must distinguish between the volumes which were put together many years later and the album which was compiled closer to the time of the events being recorded. It seems to have been Jack Clennell who used three ring-binders to set out the family story by way of photographs and typed captions, and this may well have been done to accompany the account which he was writing at a time when memories of the treaty port world were fast fading.[22] Viewed alongside its early chapters, the images are designed to conjure up the family’s life in China and scenes of a happy childhood but, possibly also to record the less happy years he had spent as a teenager, separated from his parents in the early 1920s.

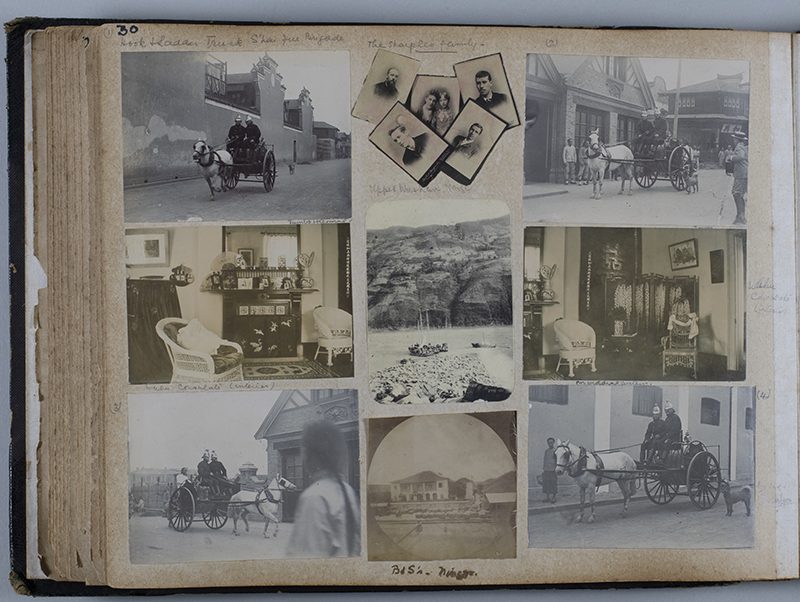

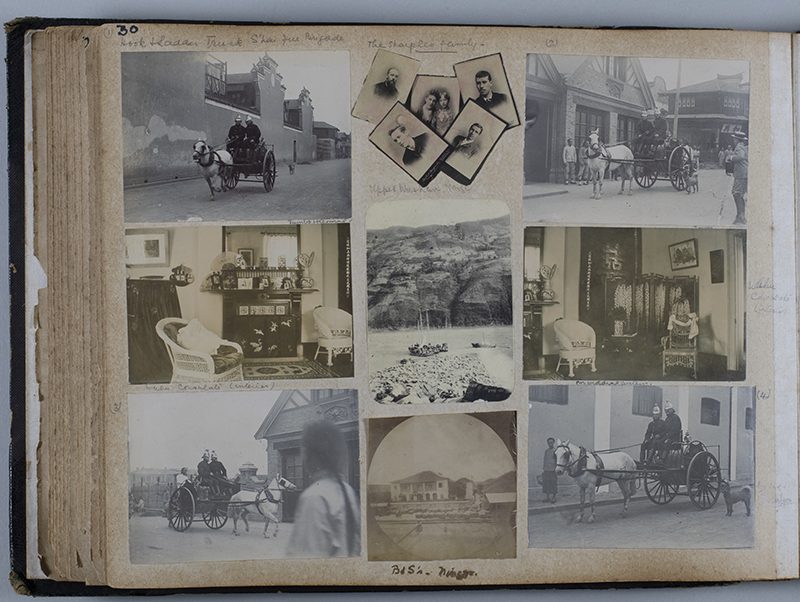

14. A page from the Clennell album compiled contemporaneously, depicting various members of the Sharples family, the ‘Hook and Ladder Truck’ of the Shanghai Fire Brigade in which Ernest Sharples served, the interior of the Wuhu Consulate where the Clennells began married life, the Upper Wushan Gorge on the Yangzi, and Butterfield and Swire’s premises at Ningpo, where Ernest Sharples was working at some stage; HPC CF03-p.30

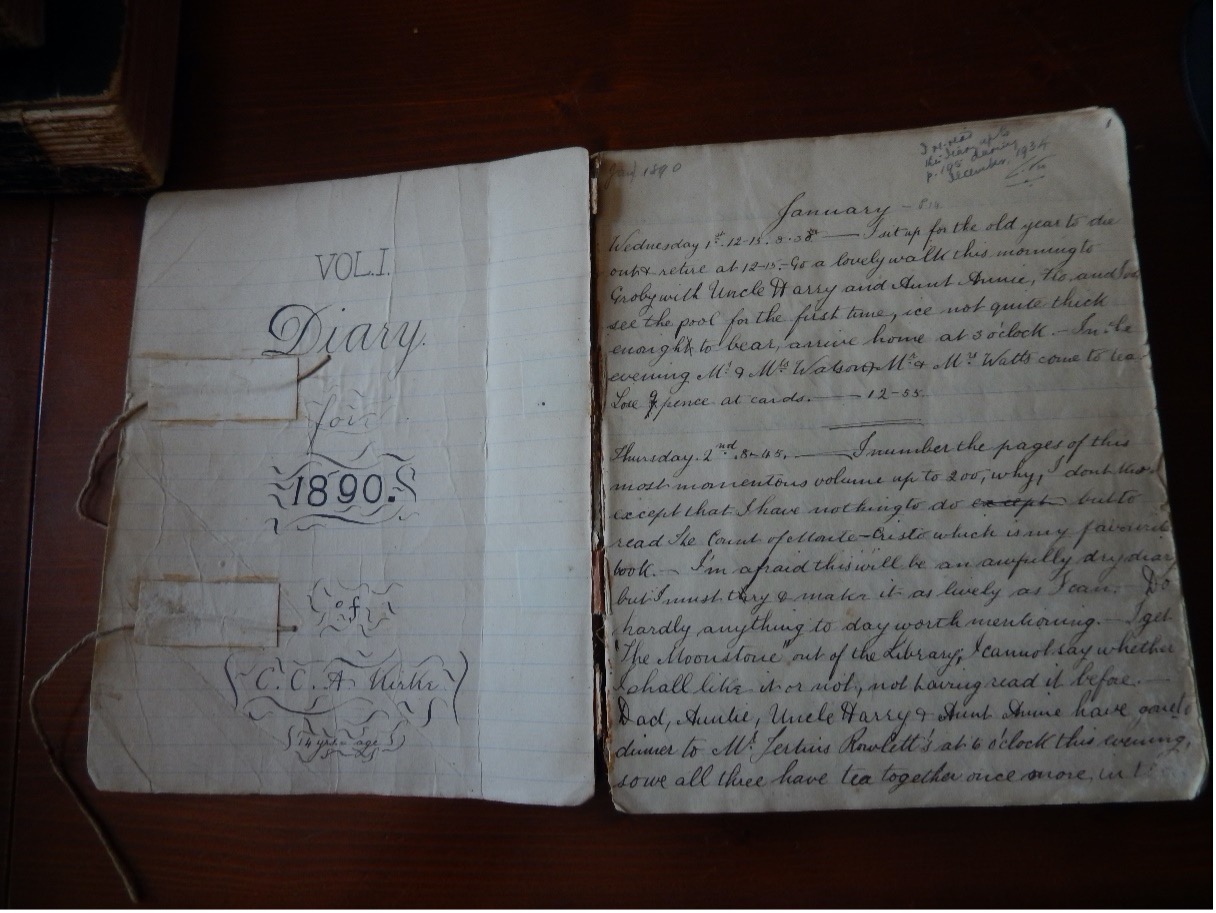

However, it is the album in which photographs were pasted when the family was in China that best conveys the significance of this sort of artefact. Scuffed and a little untidy, it is greater than the sum of its parts, showing as it does the importance of family in this type of overseas setting and the way such images could knit together the various strands of life threading through the treaty ports and back home to England. Preserved by good fortune, it must be typical of so many albums compiled by similar consular families, which reflected and reinforced the networks underpinning the British World, but few of which seem to have survived.

—-

My Dearest Martha: The Life and Letters of Eliza Hillier (edited with an Introduction by Andrew Hillier) was published by the City University of Hong Kong Press in July 2021. Andrew is currently researching for a book on the wives of China consular officials.

https://www.andrewhillier.org/

[1] For Walter’s life as a Student Interpreter, see Andrew Hillier, ‘The Kodak Comes to Peking’. Following an overland journey from Xiamen (Amoy) to Fuzhou (Foochow) and back in December 1892, the Minister, Sir John Walsham, forwarded Clennell’s report to the Foreign Secretary, the Marquis of Salisbury, commenting that he had ‘evinced great interest in the country and possesses many of the qualities requisite to render him a successful traveller and a careful observer of the customs and habits of the people’; Report by Mr Clennell of an Overland Journey From Amoy to Foochow and Back, presented to both Houses of Parliament, August 1892, including letter, Walsham to Salisbury, 14 March, 1892, C-6814.,

[2] All images are from the Walter Clennell Collection. The Collection has now been digitised by Historical Photographs of China and will in due course form part of the web-site’s Collections. HPC is extremely grateful to Richard Clennell (one of Jack Clennell’s sons) for allowing the albums to be copied and made accessible. I am grateful to Richard and his wife, Joan, for allowing me to pore over the photographs in their home and to Jonathan Clennell (son of Jim Clennell) for first alerting me to Walter’s diary and the fascinating family story.

[3] Cf. P.D. Coates, The China Consuls: British Consular Officers, 1843-1943 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 99-100.

[4] Herbert Sharples had joined the Maritime Customs Service and, by the time of his retirement in 1924, was a Customs Commissioner. Ernest Sharples had joined Butterfield and Swire and would become a well-known figure in the treaty port world, serving in the Shanghai Volunteer Corps and as ‘an ardent fireman’ in the city’s fire brigade, but die at the age of forty-seven; see his short obituary in North China Herald, 22 September 1917, 664.

[5] Robert Bickers, The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914 (London: Allen Lane, 2011), pp.339 -354, Coates, The China Consuls, pp.372-5.

[6] Robert Bickers, ‘The Lives and Deaths of Photographs in China’ in Christian Henriot and Weh– hsiu Yeh (eds), Visualising China, 1845 -1965: Moving and Still Images in Historical Narratives (Leiden: Brill, 2012), quote at p.18 and pp. 25-29; for the interpretation of family photographs, see Julia Hirsch, Family Photographs: content, meaning and effects (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), pp. 11-13.

[7] Coates, China Consuls, p. vii; cf. Andrew Hillier, Mediating Empire: An English Family in China, 1817-1927 (Folkestone: Renaissance Books, 2020), pp. xxi-xxix.

[8] Coates, China Consuls, pp.279-280.

[9] North China Herald, 17 April 1899, p. 65.

[10] Although Edie and Frank were rescued in this way, the detail in the caption is not borne out by the reference to Gregory Haines, Gunboats on the Great River (London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1976).

[11] Clennell to Satow,2 August 1905, TNA PRO 30/33 8/13, Ian Ruxton (ed.), Correspondence of Sir Ernest Satow, British Envoy in China (1900-1906), vol. 2, p. 459

[12] Coates, China Consuls, pp. 391-2, Bickers, The Scramble for China, p.339.

[13] Clennell to Satow, 2 December 1905, TNA PRO 30/33 8/6, Ruxton (ed.) Correspondence of Sir Ernest Satow, (2), p.217. The Qingdao-Jinan line was financed by German capital but was not yet completed.

[14] Connie was married to Captain Lewis Tobias Loftus Jones, R.N.

[15] Walter John Clennell, Eastern Odyssey (Douglas: Jacla Press, c.1989), p.11. Walter and Edie had climbed the mountain the previous year and Walter had written an account of their holiday exploring Lu, the Holy Land of Confucianism, North China Herald, 13 September, 1907, p.638.

[16] Coates, China Consuls, p.292.

[17] North China Herald, 25 September 1915, p. 829, 22 April 1916, pp.144-5, 14 April 1917, 76.

[18] Walter James Clennell, The Historical Development of Religion in China (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1917).

[19] Memories of China, Herts Mercury, 1 December 1950, CF01-34.

[20] Jenny Huangfu Day suggests that this may be a rendering of Walter’s surname as 乐念乐 (le-nian-le), with the middle character meaning “thinking of” or “missing.”

[21] Cf. Bickers, ‘The Lives and Deaths of Photographs in China’, p.18.

[22] The ring-binders are referenced as HPC, CFO1, CFO2 and CFO4 and the original album as CF03. There is also a small album of postcards, CF-05.

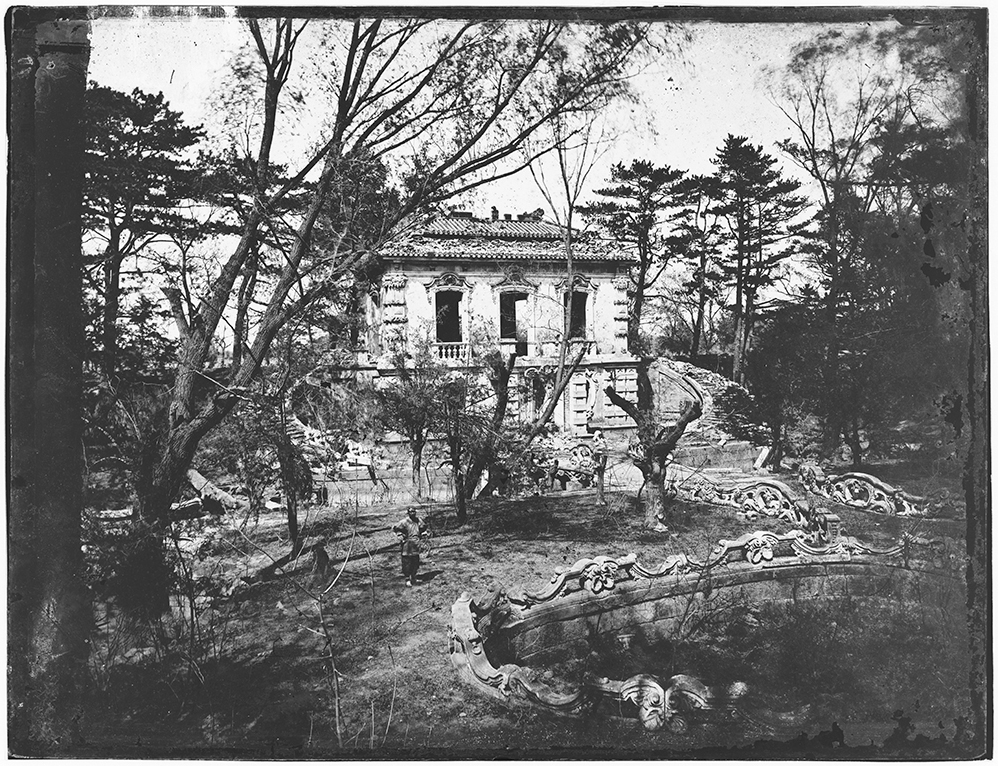

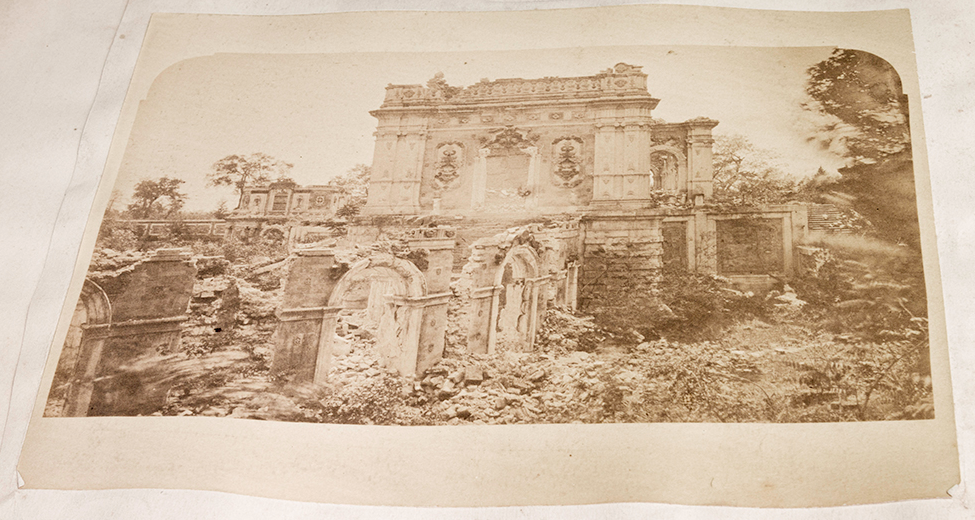

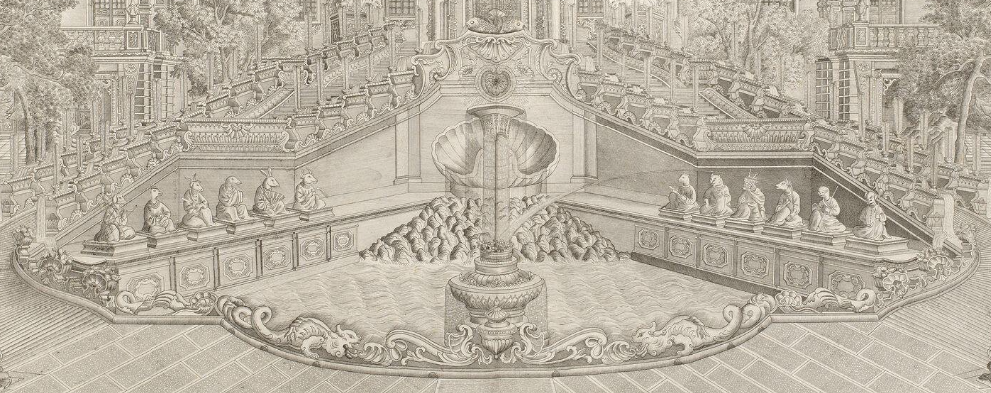

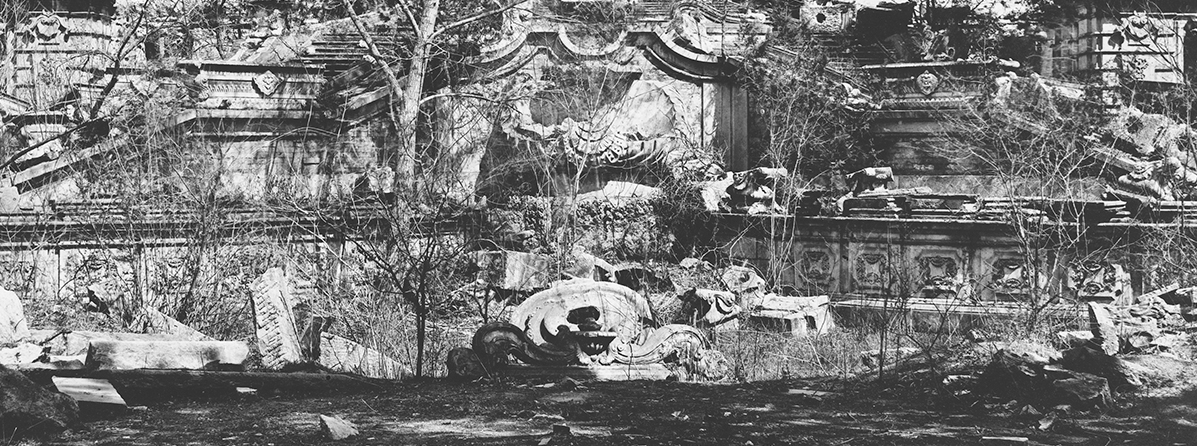

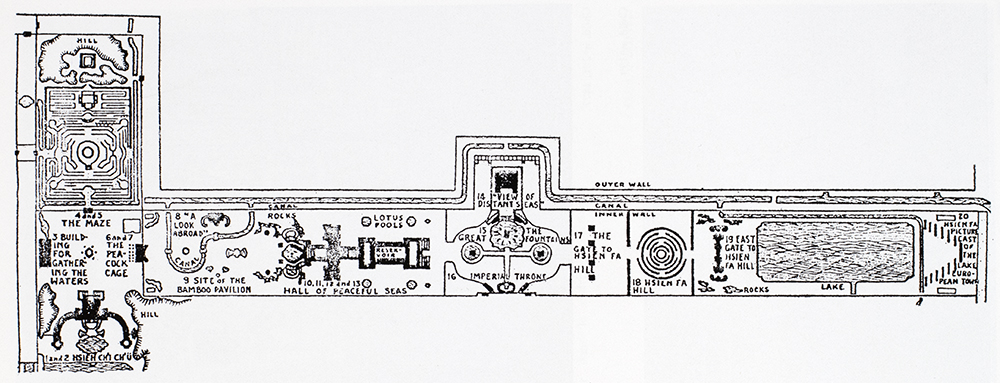

![Fig 8. The 'Palace of the Delights of Harmony' (Xieqiqu), Yuanmingyuan, viewed from the south, across the weed choked pool, reflecting the ruins of the palace. Two men are posed by the balustrade around the pool. This print was made with an indented rounded corner mask (i.e. a 'signature' of Moore's) and captioned: ‘Bâtiment principal construit par […] a Yuen Ming Yuen / Etat 1879 d'après Moore / 26 / 19’. This is a key photographic print/captioning, connecting Moore's name with the rounded corner mask, strategically placed people, as well as showing more from his (lost) negative than other prints. A well composed and frequently reproduced photograph, its punctum, for many, being the reflection of the ruin in the water. Source: Part of Lot 2, in an auction by Tessier & Sarrou et Associés, Paris, on 17 December 2018.](https://hpchina.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2022/05/Annotation-2022-05-18-180749.jpg)

![A Cartier-Bressonesque photograph by Cyril Whitaker, captioned in the album: ‘Calibrating a [petroleum] tank by pumping out and weighing water on alternate scales. Jan. 1938’ (HPC ref: CW08-80). Whitaker was a talented ‘semi-pro’ photographer who documented the Asiatic Petroleum Company (APC) installation near Chongqing. Cyril Whitaker Collection, DM2845/8.](https://hpchina.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2022/01/12.-CW08-80.jpg)