Lauren Walden is currently a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Contemporary Chinese Art at Birmingham City University. Her PhD in Art History from Coventry University explored the global expanse of Surrealism in relation to cosmopolitan theory, including the advent of Surrealism in China. In 2018, she was awarded the Gary Metz fellowship to conduct research on Mexican Surrealist Lola Alvarez Bravo at the Centre for Creative Photography in Arizona, and was also recipient of a Visiting Research Fellowship at the Henry Moore Foundation in Leeds (2019) for research on to the Surrealist reception of African art. Lauren is currently working on a short book project with the Fondation Giacometti in Paris which investigates Surrealism in Shanghai’s former French Concession.

Emblematic of Shanghai’s elite cosmopolitanism during the modern era, the Cercle Sportif Français (CSF) became the first foreign-owned club to admit women, Chinese and other nationalities into its highly select coterie, provided the necessary status or financial means were at one’s disposal.[1] Founded in 1905, the club’s original premises rapidly became too small for its burgeoning membership. In 1920, the club’s President Henri Madier, asked the French Concessions’ municipal administration for permission to construct a new building on parkland in an area known as the Jardin de Verdun.[2] Whilst the CSF was, for all intents and purposes, a private members club, it nevertheless received substantial financial support from the Municipal Council of the French Concession.

After three years of contractual negotiations, the club and the municipal administration agreed to the following terms: The municipal administration bought the CSF’s original premises for 170,000 taels on the Route Vallon and ceded its own municipal land on the Jardin de Verdun for just 2000 taels per mou (665 m²).[3] Fredet notes that the club building was constructed on 4200 m² of terrain, approximately 6 mou. Although the total surface area of the Jardin de Verdun came to 45,000 m² or approximately 60 mou, the contract stipulates that land beyond the club building itself remained municipal property but would be rented to the CSF for a token sum of 1 tael per year.[4] The total expenses accrued for the construction and interior design of the new club came to 700,000 taels.[5] In spite of these favourable conditions, the municipal administration required that the CSF’s committee must remain French or they would have the right to forcibly repurchase their land.[6] Whilst the club’s admissions policy was more open than its other imperialist counterparts, it is clear that the French Concession municipal council was prepared to leverage financial expenditure in order to enrich the symbolic economy of French colonialism and its patriotic rayonnement to Shanghai’s numerous communities. In a sense, the CSF was France’s unofficial consulate in Shanghai, certainly in terms of propagating ‘soft power’ in an attempt to legitimise the French colonial presence in the city.[7]

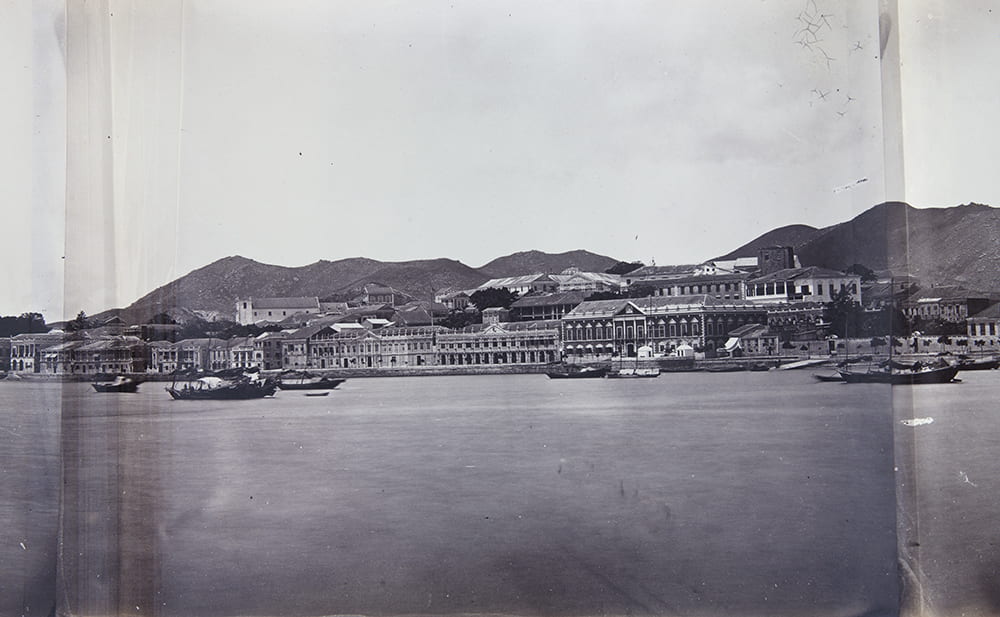

Figure 1. Cercle Sportif Français, Shanghai, circa 1926. Image reproduced in ‘Shanghai of Today: a Souvenir Album of Thirty-eight Vandyke Prints of ‘The Model Settlement’’ (A. S. Watson & Company, Shanghai, 1927), plate 37. Image courtesy of Historical Photographs of China, University of Bristol (HPC ref: Bk46-37).

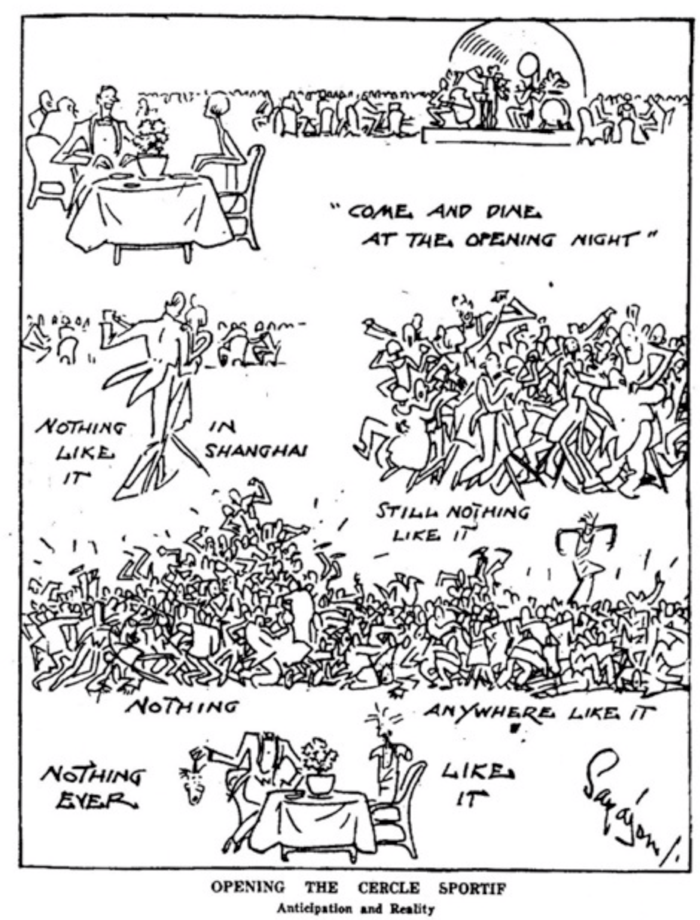

The contract was signed on the 21 November 1923 and Shanghai-based French Architects Leonard and Veysseyre constructed the new building between 1924 and 1926 (Figure 1). The building was inaugurated on the 30 January 1926, an event parodied by Russian cartoonist Sapajou, himself a member of the club, in the North-China Daily News (Figure 2). It seems that on the opening night the CSF’s pretence towards grandeur and civility quickly declined into an immense melee, China Press reporting circa 1,200 guests in attendance.[8] Andrew Field notes ‘the dignity of the club and the French Nationalist sentiments that it attempted to project could not match the Jazz Age nightlife culture that Shanghai had adopted during the 1920s’.[9] Arguably, it was precisely the simultaneous combination of decorum and decadence that cemented the club’s success, hedonistic pursuits subsumed by the opulent splendour of the club’s grounds. Moreover, the French consul general, M. Meyrier indirectly invoked the goal of ‘soft power’ at the heart of the CSF’s conception. His speech at the inaugural reception affirmed that the CSF: ‘has provided for the French and Foreign communities the means of a most amiable understanding, social intercourse, and that atmosphere of charm which Talleyrand said was the secret of all diplomacy’.[10] Therefore, we can perhaps surmise that inculcating a cosmopolitan, jazz-age environment at the CSF actually served to further the goals of French nationalism, distinguishing its ‘brand’ of colonialism from the British-dominated international concession.

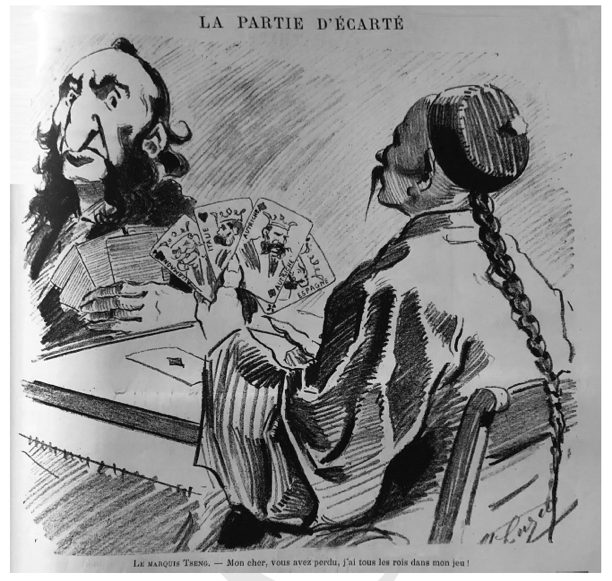

Figure 2. ‘Opening the Cercle Sportif — Anticipation and Reality’ by Sapajou, reproduced in Richard Rigby ‘Sapajou’s Shanghai’ China Heritage Quarterly, 2015.

Within the Historical Photographs of China collections, a photograph in the collection of British-American Tobacco graphic artist Jack Ephgrave preserves the dignified aspect of the club, depicting the grandeur of its neo-classical façade and expansive grounds, mainly used for tennis, through an aerial shot in 1927 (Figure 3). A second photograph, likely taken by Ephgrave himself, captures the Olympic size swimming pool measuring 54 x 10 metres, flanked by many spectators (Figure 4). Born in 1914, Ephgrave photographed many exclusive sights in Shanghai emphasising the cultural mobility of his family within the cityscape. Interestingly, despite his clear association with Britain, Ephgrave does not photograph the rival British Shanghai Club which had a highly restrictive admissions policy and more austere atmosphere, the CSF was more family-orientated than its British counterpart.

Figure 3. Aerial View of the Cercle Sportif Français (French Club) Shanghai, 1927. Image courtesy of Adrienne Livesey, Elaine Ryder, Irene Brien and Historical Photographs of China, University of Bristol (HPC ref: Ep01-006).

Figure 4. Swimming Pool, Cercle Sportif Français (French Club), Shanghai, 1929. Photograph attributed to Jack Ephgrave. Image courtesy of Adrienne Livesey, Elaine Ryder, Irene Brien and Historical Photographs of China, University of Bristol (HPC ref: Ep01-193).

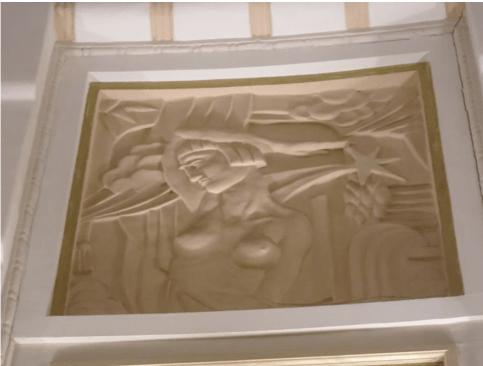

Beyond the grounds and swimming pool photographed by Ephgrave, whether or not the club was truly ‘sportif’ in nature is highly questionable. Other facilities included a billiard room, reading room, canteen, restaurant, ballroom, tea room, card room, private salons, bars and a roof terrace. The neo-classical exterior of the CSF is somewhat offset by its more hybrid interior where art deco style dominates, interspersed with neo-classical touches. The dichotomy of style between the interior and exterior of the building appears symptomatic of the French art and architectural scene at the time, torn between recourse to ancient Greco-Roman civilisation and the geometric simplification of form characteristic of art deco. Tess Johnston draws attention to the ‘plasterwork friezes of statuesque nudes’ which populate modernist columns in the entrance hall.[11] The nude here is identified by Fredet as a caryatid, a voluptuous female figure serving as the support for a column in ancient Greece (Figure 5).[12] In contrast, a cubist-inspired frieze of a sojourning nude modern girl with a flapper haircut and geometricized anatomy also adorns the ballroom, the interior design of the CSF undoubtedly commingled the ancient and the modern (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Interior columns in the CSF, 2015. Photograph by David Thompson.

Figure 6. Frieze in the CSF, 2015. Image courtesy of Tina Kanagaratnam, Shanghai Art Deco Society.

Further to this, the ballroom boasts an iconic, multicoloured stained-glass light, an original feature cited by Fredet in 1926.[13] Light refracting through the prism of this elliptical feature would dazzle on the ballroom floor (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Stained Glass light in the Ballroom of the CSF, 2015. Photograph by

David Thompson.

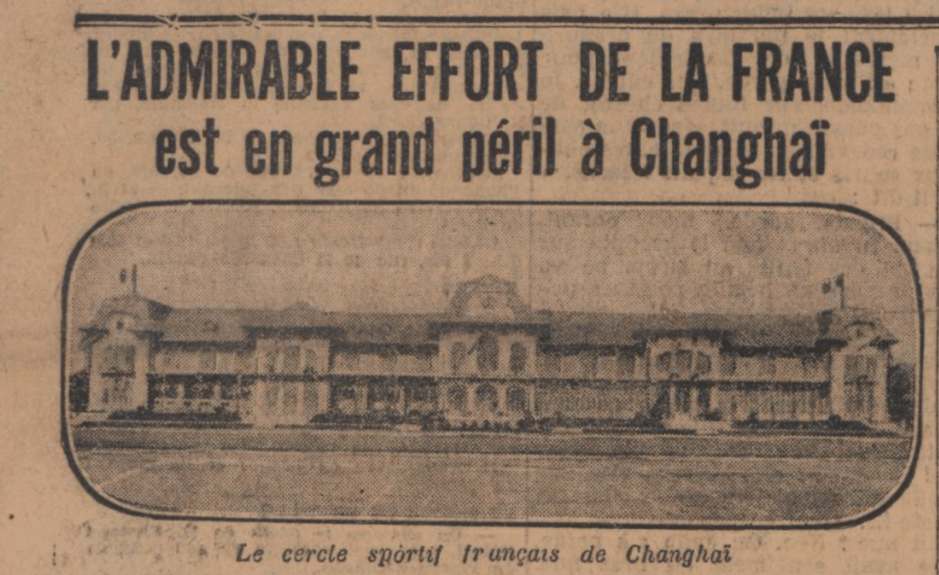

The symbolic value of the club was employed in the French metropole as a justification of nation’s ‘mission civilisatrice’ (civilising mission) in its colonial territories. One bizarre article dominating the front page of French paper Le Journal in February 1927 laments that the ongoing conflict in Shanghai relating to workers strikes and the rise of the communist party would negatively affect the club.[14] The headline translates as ‘The admirable effort of France is in grave danger in Shanghai’ with a picture of the CSF underneath (Figure 8). The reporter Pierre Benoit, having visited the club states: ‘Parisian newspapers have long been predicting the imminent fall of Shanghai, an event with incalculable consequences, the hardest hit for a long time against European prestige’.[15] A potted history of the Shanghai French concession then ensues with the CSF being presented as France’s latest undertaking in Shanghai. As such, the CSF is portrayed as the apotheosis of all of France’s achievements in the city.

Figure 8. Le cercle sportif français de Changhai, ‘Le Journal’, 21 February 1927.

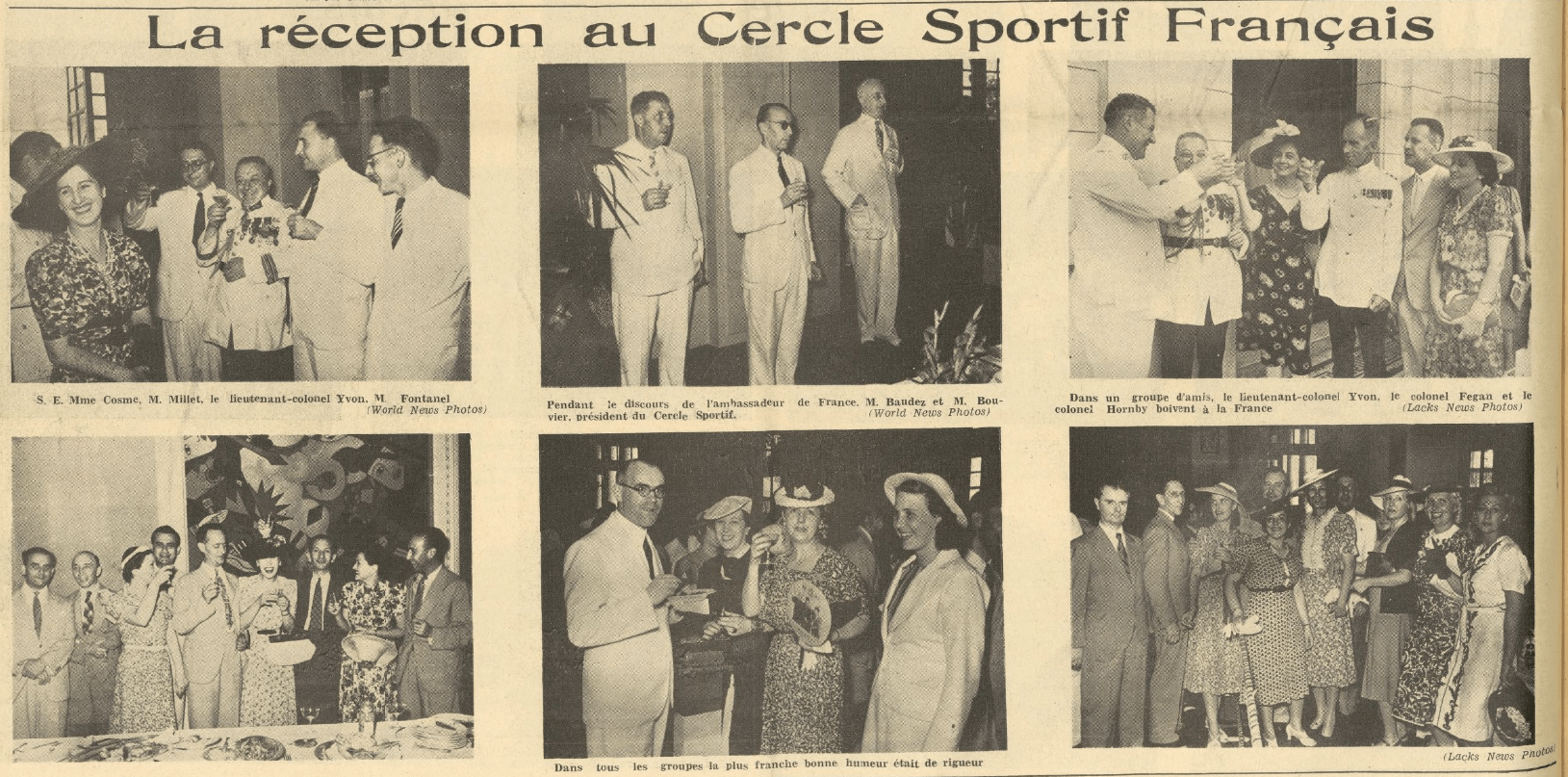

In terms of French soft power, the most important event of the club’s social calendar was undoubtedly le quatorze juillet or Bastille day celebrating the French Revolution of 1789. Festivities commenced from 1pm in the afternoon late into the night. The reception at the CSF was reported on an annual basis in the francophone language newspaper Le Journal de Shanghai (a newspaper also subsidised by the French Municipal administration). The French consul or vice-consul would usually attend the reception and the club president would give a speech particularly addressed to predominantly non-French club members in attendance. In 1933, Le Journal de Shanghai published an image of the reception at the club, the tricolore adorning the hall (Figure 9). The reporter emphasises both the cosmopolitan nature of the guests alongside the efforts made to promote French soft power: ‘A veritable cornucopia of all races, people came from all four quarters of the world to celebrate bastille day … Once again the French concession has worked hard to maintain and further promote the prestige of France’.[16] Whether or not the club could truly purport to host a cornucopia of races in 1933 is highly questionable. Glaise, who has consulted a file on the CSF at the Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes has revealed that in 1933 the club had 1,098 male members and 729 female. In terms of nationality, Glaise reports the following breakdown:

164 French, 490 English, 168 Americans, 27 Italians, 40 Dutch, 50 Danish, 10 Swedish, 11 Norwegian, 15 Belgian, 41 Russian, 7 Hungarian, 2 Syrian, 1 Turkish, 5 Austrian, 1 Cuban, 1 Romanian, 13 Swiss, 4 Portuguese, 3 Latvian, 3 Polish, 6 Spanish, 4 Finnish, 3 Greek, 2 German, 9 Japanese, 16 Czechoslovakian, 1 Bulgarian.[17]

Whilst the club did transcend both gender and national boundaries, a notable omission is a lack of Chinese citizens being recorded on the club’s roster. Hence, it seems that more of a theoretical rather than empirical cosmopolitanism prevailed with regards to the club’s host nation.

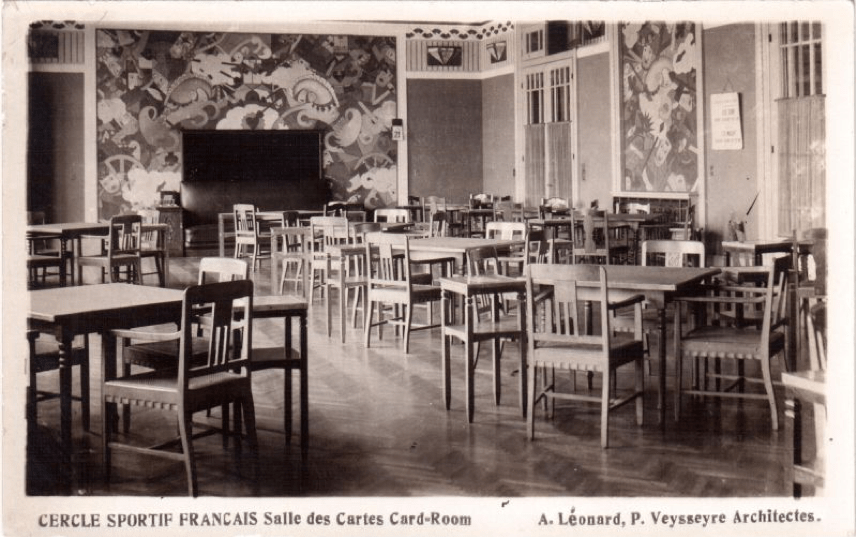

Interestingly, reporting of the annual reception became more prominent after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese war when the foreign concessions entered their 孤岛 or ‘lone island’ phase, shielded from the conflict. In a large spread in 1939, an avant-garde artwork adorns the wall in one photograph, revellers with their glasses raised. The newspaper reported 800 people attending.[18] If we cross reference the avant-garde murals in the bottom left photograph (Figure 10) with the architect’s image (Figure 11) we can deduce that this was the card games room of the circle. Katya Knyazeva reveals that a large proportion of the CSF’s interior design can be attributed to Shanghai’s Russian diaspora, many of whom resided in the French concession: ‘V. Podgoursky designed coloured glass windows in some of the rooms; M. Stupin painted modernist murals; V. Shibaeff created the sculptures above the fireplace in the library.’[19] Granted the North-China Daily Herald also describes Stupin’s murals as modernist, it is most likely he is responsible for those in the card room.[20] It appears that the avant-garde work incorporating fragments of playing cards, was deliberately chosen to reflect an atmosphere predicated on chance, luck and enjoyment, also populated by the leitmotiv of masks.

On Bastille day in 1939, during the club’s president’s annual speech M. Bouvier, invoked ideas of universalism:

We can affirm without fear that in these troubled times we are living through, this celebration assumes a symbolic character, rallying people from all nations who wish to live in freedom and safeguard the dignity of the human being, rallying all those who believe that all nations, all mankind has the right to liberty, rallying all those who wish to base the progress of the human condition on universal cooperation.[21]

This speech was of course given before the Nazi invasion of France and the takeover of Shanghai’s French municipal council by the Collaborator Vichy regime.

Figure 11. Card Room, Cercle Sportif Français, circa 1925. Image courtesy of Tess Johnston, reproduced in Johnston, Tess, and Deke Erh ‘Frenchtown Shanghai: western architecture in Shanghai’s old French concession’ (Old China Hand Press, Hong Kong, 2000), p.104.

Indeed, the fate of the club was inextricably linked to that of the French Concession during World War Two, its enviable soft power unable to save it from military occupation by the Japanese in December 1941. After the liberation in 1949, the CSF first became a People’s palace and was subsequently used as a private guesthouse by Mao Zedong, the nude figures populating its interior ‘all covered with plywood during the cultural revolution’.[22] Whilst the CSF clearly transcended many colonial antinomies in terms of both national and ethnic divisions, the relentlessly hierarchical admissions policy coupled with the extreme gap between Shanghai’s rich and poor during the Republican era ensured that its soft power amongst the elites of the city equally epitomised everything the Communists despised about Shanghai . It is clearly not a coincidence that this building was symbolically re-appropriated into a people’s palace which would, like its predecessor, operate a restrictive admissions policy. Model workers became the new Shanghai elite with exclusive access to the club.

The former CSF is now the Okura Hotel owned by a Japanese company which has preserved many of its original features. In terms of the club’s cultural memory, today it is not so much remembered as a bastion of imperialism, although this was clearly what the French municipal council intended, but rather for its innovative art deco interiors which been safeguarded as an important piece of cultural heritage. As such, the legacy of soft power enjoyed by the former Cercle Sportif Français continues to this day.

[1] Women were first admitted to the club in 1907. See ‘Inaugural Ceremonies of New French Club Held’ The China Press, 31 January 1926, p.7.

[2] Compte rendu de la gestion pour l’exercice 1920 – Budget 1921 – Conseil d’administration municipale de la Concession française, p.70.

[3] Compte rendu de la gestion pour l’exercice 1923 – Budget 1924 – Conseil d’administration municipale de la Concession française, p.248-249.

[4] Jean Fredet ‘Le Cercle Sportif de Changhai’ L’Illustration, 30 October 1926, p.476; Compte rendu de la gestion pour l’exercice 1923 – Budget 1924 – Conseil d’administration municipale de la Concession française, p. 249.

[5] Jean Fredet ‘Le Cercle Sportif de Changhai’ L’Illustration, 30 October 1926, p.476.

[6] Compte rendu de la gestion pour l’exercice 1923 – Budget 1924 – Conseil d’administration municipale de la Concession française, p. 249.

[7] Joseph Nye explains ‘Soft Power’ in the following terms: ‘Soft co-optive power is just as important as hard command power. If a state can make its power seem legitimate in the eyes of others, it will encounter less resistance to its wishes. If its culture and ideology are attractive, others will more willingly follow. If it can establish international norms consistent with its society, it is less likely to have to change. If it can support institutions that make other states wish to channel or limit their activities in ways the dominant state prefers, it may be spared the costly exercise of coercive or hard power’: Nye, Joseph S. “Soft Power.” Foreign Policy, no. 80 (1990): 153-71.

[8] ‘Inaugural Ceremonies of New French Club Held’, The China Press, 31 January 1926, p.7.

[9] Field, Andrew. 2010. Shanghai’s dancing world: cabaret culture and urban politics, 1919-1954. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p.33.

[10] ‘Inaugural Ceremonies of New French Club Held’, The China Press, 31 January 1926, p.7.

[11] Johnston, Tess, and Deke Erh. 1998. A Last Look: Western architecture in old Shanghai. Hong Kong: Old China Hand Press. p.38.

[12] Jean Fredet ‘Le Cercle Sportif de Changhai’ L’Illustration, 30 October 1926, p.477.

[13] Jean Fredet ‘Le Cercle Sportif de Changhai’ L’Illustration, 30 October 1926, p.477.

[14] The Communists would be brutally purged from the city under the orders of Nationalist party leader Chiang Kai-Shek two months later in collusion with the administration of Shanghai’s international settlement, prompting their ruralisation.

[15] Pierre Benoit ‘L’admirable effort de la France est en grand péril à Changhai’, Le Journal, 21 February 1927, p.1.

[16] L.C ‘Le Quatorze Julliet à Shanghai;’ Le Journal de Shanghai: organe des intérêts français en Extrême Orient, 16 July 1933, p.8.

[17] Glaise, Anne Frédérique. 2005. L’évolution sanitaire et médicale de la concession française de Shanghai entre 1850 et 1950. Thèse de doctorat: Histoire: Lyon 2: 2005. p.133 It would appear that this breakdown of nationality only appears to correspond to the number of male members.

[18] ‘Le Bal au Cercle Sportif Français’, Le Journal de Shanghai: organe des intérêts français en Extrême Orient, p.7.

[19] Katya Knyazeva, 2020. ‘Building Russian Shanghai: The Architectural Legacy of the Diaspora’ The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China, 80:1 p.175.

[20] ‘Opening of the New French Club’, North-China Herald, 6 February 1926, p. 236.

[21] ‘Au Cercle Sportif Français’, Le Journal de Shanghai: organe des intérêts français en Extrême Orient, 16 July 1939, p.12.

[22] Johnston, Tess, and Deke Erh. 2000. Frenchtown Shanghai: western architecture in Shanghai’s old French concession. Hong Kong: Old China Hand Press. p.105.